Bird ringing is a way to monitor the survival rates and movements of birds. It is a simple concept which involves attaching a coded metal or plastic ring to the leg of a bird, recording several measurements and observations, then releasing. Although simple it requires significant skill and training to ensure the safety of the birds. If the bird is recorded again in the future it adds a little piece of information to the bigger picture. A vital tool for focusing conservation efforts, it provides an in-depth understanding of population changes and can help to pinpoint the causes of declines.

Since 2012 Biotope has organised annual ringing camps in Varanger, in collaboration with the UK-based Wychavon and Brewood ringing groups. Biotope is an architectural practice in Vardø specialising in outdoor architecture and destination development projects. Since 2009 we have been working on the development of Varanger as a birding destination and raising awareness of the region’s rich and unique birdlife. We approach our work with the key aims of involving and enthusing local communities to care about and take responsibility for their local environments. We work closely with local scientists and tourism companies to bring nature and environmental issues to the forefront of local awareness. Varanger is unrivalled in Europe for its easily accessible arctic birdlife and there is no better way of bringing people face-to-face with it than bird-ringing demonstrations. We have arranged these at all of our ringing sites: from Gullfest in Vardø, to our ringing camps in Nesseby and Pasvik. These demonstrations provide an exciting experience for local schoolchildren, which can be seen in their reactions to seeing the birds up close. This is especially fulfilling when they can be repeated over a number of years. At Gullfest in Vardø, kids are able to meet, and follow the progress of their local gulls and kittiwakes year on year, resulting in them becoming more conscientious and aware of their local environment.

Since the beginning of the project in 2012 a cumulative total of 21,000 birds of 72 species have been ringed in Nesseby, Vardø and Nyrud (Pasvik). Consistent annual ringing has not taken place at these sites and ringing totals have varied widely owing to a variety of factors, including trip timings and weather.

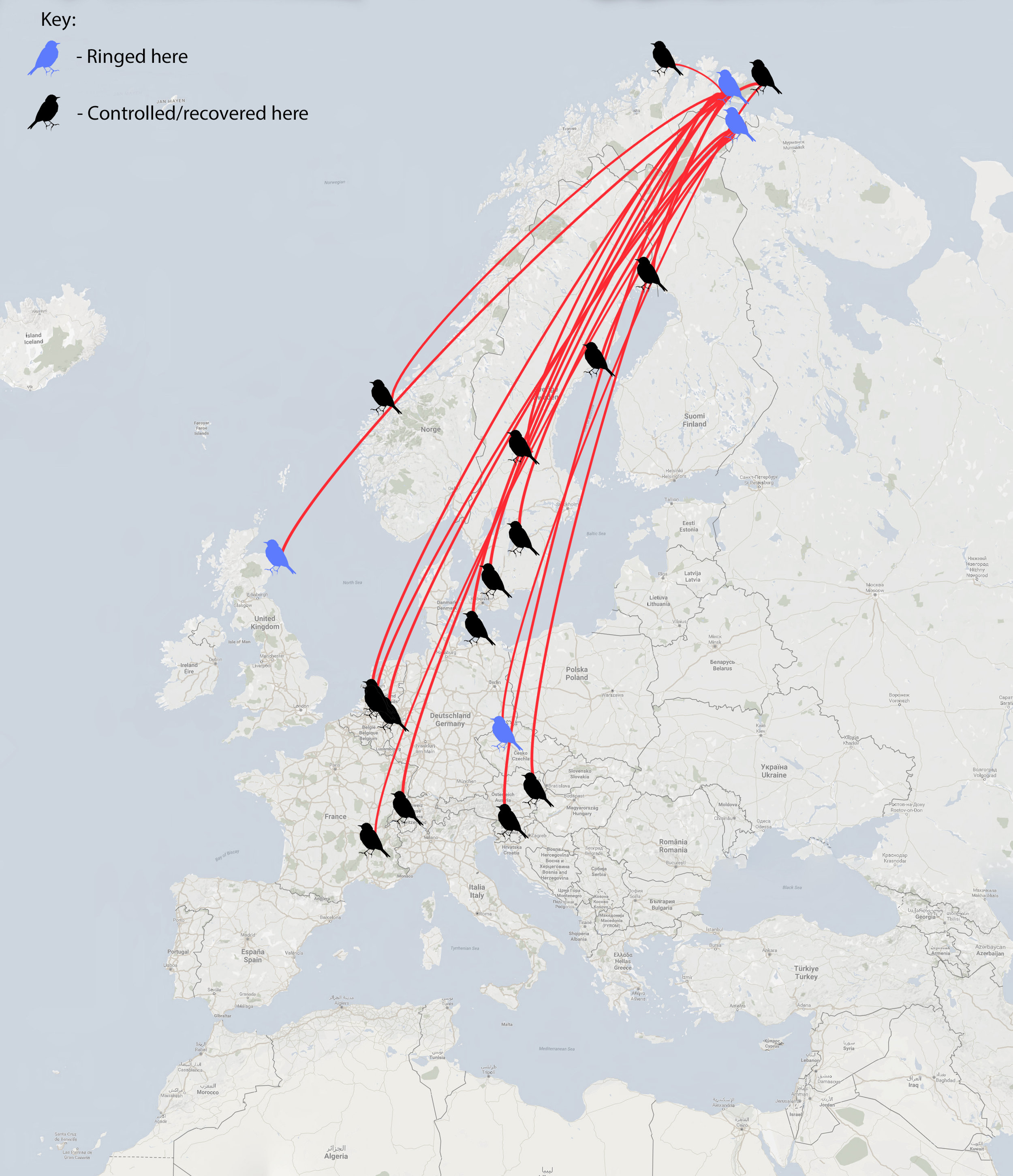

The continued aim of this project is to contribute towards a greater understanding of the importance of Varanger for different bird species and their migration routes throughout Europe and beyond. Thanks to the large number of birds ringed, we have had a number of recoveries from different parts of Europe. This data is useful in understanding the migration strategies of birds ringed in Varanger and particularly for comparing to different parts of the birds’ ranges. In the long term it could also help us to understand the effects of climate change on the region’s birdlife.

Ringing recoveries from Varanger.

Nesseby

Nesseby has long been considered a top migration site within Varanger, due to its location near the base of the Fjord, which acts as a funnel for birds migrating southwards out of Varanger. Although the ringing dates have varied each autumn, the data still provides an insight into the variety and numbers of birds using the site on their southward migration. In a 32 day period in 2014 an impressive 6648 birds were caught and on the best day, 16th September, 703 birds were trapped. Birds ringed at Nesseby have been recovered from as far away as Switzerland and Slovenia, and most of the recoveries have been of first calendar-year birds moving south in the autumn.

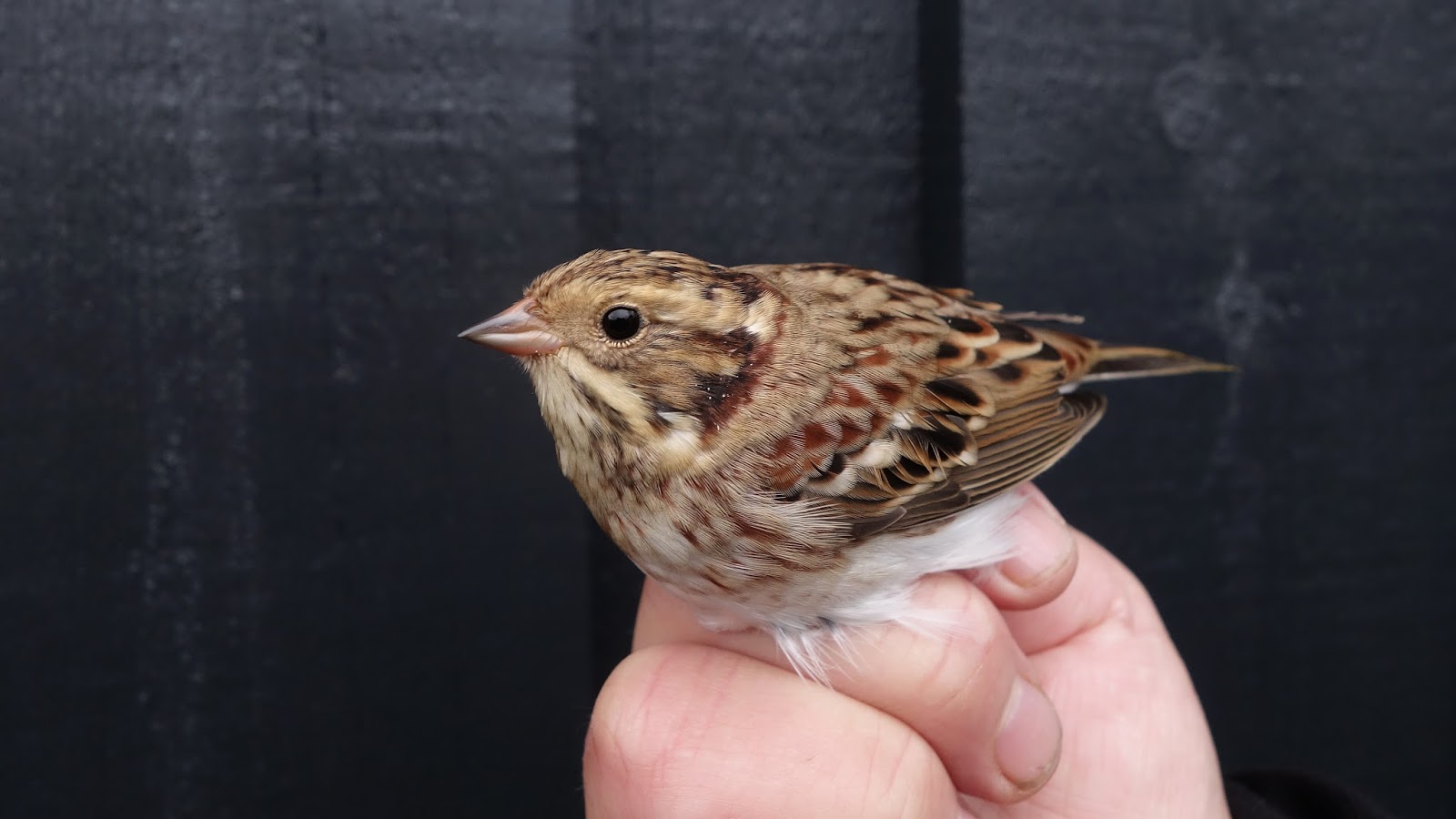

Along with the common species such as meadow pipit and mealy redpoll, some rarer species have turned up in the nets. In 2013 a thrush nightingale was caught, the first and still the only record for Finnmark; a rustic bunting was caught the same year, a rare bird in Norway which is declining globally. In 2014 a barred warbler was caught, also the first record for Finnmark.

This site is obviously worthy of further studies, but due to logistics we were not able to continue ringing at Nesseby in 2017, investing more effort into ringing in Pasvik and Vardø instead.

Pasvik

The key difference between Pasvik and the other two sites is the extensive and often uniform forest habitat, with birds moving through on a broad front. This makes finding the best mist netting sites a more difficult task as birds can be moving through almost anywhere. In 2015 the team was lucky that the level of the Pasvik river was low enough that nets could be put up in the riverside willows, where migrants are more concentrated. This, we believe, was the key contributory factor to the very large catch that year (although the earlier dates will also have coincided with peak passage). Higher water levels have meant it has not been possible to operate nets in this habitat in the last two years; with much smaller catches as a consequence.

Another interesting observation is that, of the 3893 birds caught in 2015, not a single one was re-trapped, perhaps indicating that the birds using this type of habitat are literally using it as a migratory ‘highway’ through the forest. In the following two years a vastly higher proportion of the birds were re-trapped on days prior to catching, suggesting that birds were lingering longer in the woodland, and there were a higher proportion of resident species too. In 2016, out of 15 re-traps, 12 were from the previous year with only three re-traps from the current year (there were also 3 Russian control great tits from the ringing station at Varlam Island in Russian Pasvik). In contrast, out of 13 re-traps in 2017, only one was from 2016, with the other 12 from the current year (as well as two Russian controls). Species composition has also varied between the years, which is likely to be the result of ringing on different dates and the nets being positioned in different habitats.

In the first year the visit was timed during peak passage, which occurred during August. This of course contributed to a large total catch size which was also significantly aided by trapping in the riverside willow scrub, the latter two autumn visits have both been during September. In 2016 the dates were from 08/09 to 19/09, these later dates led to a lower proportion of longer distance migrants, but larger catches of certain other species, notably tits. A number of scarce eastern passage migrants were also caught (olive-backed pipit, yellow-browed warbler and rustic bunting), these are unlikely to be passing through on earlier dates. Finally, in 2017 the dates spanned 01/09 to 09/09, predictably, this year included a higher proportion of long distance migrants than 2016, but much lower numbers again than 2015.

Over the past two years we have also been aware of a similar project being started up just over the border (defined by the Pasvik river) on Varlam Island in Russian Pasvik; just a stone’s throw from Nyrud. Their catches have largely mirrored ours in terms of species proportions and numbers, due to the similar timings of their ringing efforts and proximity of the sites. As well as this we have had some mutual recoveries such as the three great tits caught in 2016 bearing ‘Moskva’ rings. In 2017 our team attended a seminar in Svanhovd about conservation, birding and tourism in the Pasvik-Inari National Park. With representatives from all three of the involved countries (Russia, Norway and Finland) present, we were able to brainstorm ideas for future collaborations on our respective ringing projects. Further to this, Fergus Henderson (Wychavon ringing group) and Espen Quinto-Ashman (Biotope) were invited to travel over the border under special permission to take part in a small bird festival on Varlam Island. Here we met with Natalia Polokarpova (who is in charge of science and conservation work there) to see their ringing setup in action and discuss further collaborations.

Several of the birds ringed in Pasvik have been recovered elsewhere, these are shown in the table below:

Pasvik has also had its share of rarities over the three years of ringing. In 2015 the highlights were: a hawk owl, three three-toed woodpeckers and a rustic bunting. In 2016 they were: a black woodpecker (the first to be ringed in Finnmark), a yellow-browed warbler, an olive-backed pipit and a rustic bunting; in 2017 the stand out catch was six three-toed woodpeckers.

Vardø

Regular ringing began this May after Espen moved to Vardø to work for Biotope and he has been ringing there throughout the summer and autumn whenever time and weather have allowed. Having a resident ringer in Vardø has also allowed Biotope to get involved with a wider range of projects than had been possible before, where ringing had been limited to short, intensive mist netting trips. There are two main sites that are used for mist netting in Vardø: Sundammen, on Vardøya itself, and Svartnes, just the other side of Bussasundet (the stretch of water separating Vardø from the mainland). Both of the sites have willow scrub habitat, with Svartnes being more extensive and denser. When ringing alone, Espen usually operates 72m of netting at Svartnes and 42m at Sundammen; with more ringers this could of course become a much larger operation.

Svartnes

Sundammen

Aside from the mist netting we have been involved with operating various other ringing projects in Vardø, with the aim of finding out more about some of the key species that are present in Vardø. Here is an outline of some of these projects.

Purple sandpipers:

The Varanger Peninsula holds significant wintering populations of purple sandpipers, and lesser numbers breed here on higher ground. Despite the huge number of recoveries of Svalbard ringed birds in Southwest Norway and around the Baltic and White Sea coasts, only two such recoveries exist from Varanger, suggesting a low proportion of Varanger-wintering birds originate from the Svalbard breeding populations. From a recovery of a bird ringed in Skallelv in winter at Severnaya Zemlya (East Siberia) in June, combined with the comparative absence of Svalbard recoveries, we can speculate that the majority of purple sandpipers wintering in Varanger (and indeed the north and east of Finnmark) go east to breed in Siberia. Siberia’s vastness and low density of potential observers, as well as the lack of colour ringing projects on the species in east Varanger, significantly hamper our knowledge of this wintering population. Another recovery, of a bird ringed in the south of Finland on 15/12/1972 and recovered in Vadsø on 06/02/1988, is of interest as presumably it was either using different wintering areas in the different years, or more likely switched wintering sites mid-winter.

In October 2017, as an extension of an existing project in the South of Norway, we began ringing purple sandpipers in Vardø with a yellow three-letter flag on the right tibia and a red marker ring on the left tibia. This will hopefully help to answer some of the questions raised.

Leach’s petrels: A highly enigmatic species, of which relatively little is known due to their elusive habits and remote breeding locations. In Varanger they breed only on Hornøya, the most northerly known colony in the world. Despite the obvious significance of this colony, very little research has been carried out, therefore no estimates exist of the size of the colony (although it is unlikely to number more than a few dozen pairs). Past research has been limited to a few ringing trips, on one of which the researchers deployed radio transmitters and successfully located a small number of nests (thus confirming breeding on Hornøya).

Along with the Leach’s petrels are larger numbers of European storm petrels, of which even less is known in a Varanger context! On all ringing trips in the past, European has been caught in larger numbers than Leach’s, so it would seem probable that they breed in the area; but there is little to no evidence that they breed in the colony on Hornøya. This raises the question of whether there is another, possibly larger colony on neighbouring Reinøya. We hope to explore this further in 2018, as virtually no research has been done on Reinøya due to the difficulties of obtaining access permission.

In 2017 we launched a new project on the Hornøya Leach’s colony, with the aim to deploy geolocators to try and find out about another aspect of their ecology: their migration routes and wintering grounds. In a study of breeding Leach’s petrels in Eastern Canada birds were tracked to wintering grounds off the coast of Brazil and West Africa (Pollet et al, 2014), but such a study has never been done in the Eastern Atlantic. For this reason, the data gained from a geolocator study on Hornøya would be invaluable in improving our knowledge of this species and our understanding of the factors driving population declines (Leach’s petrel is classified as vulnerable on the IUCN red list of endangered species).

We were on Hornøya from 21-24th of September 2017 with Morten Helberg (from the University of Vest Agder, who has previous experience of leading trips to ring Leach’s petrels on Hornøya) with a total of 12 geolocators. We decided that this would be sufficient due to the apparently low number of birds in the colony and high recapture rate from previous years. Despite our best efforts each night we succeeded only in catching 2 of the target species (along with three European storm petrels). On the first night we caught one Leach’s petrel with our aim to attach the geolocator to the tarsus with a plastic ring, it quickly became apparent that this attachment method was not going to work (the ring was too bulky and too far from the bird’s centre of gravity), so we had to let the first bird go with no geolocator. After this setback, we looked into other attachment methods. The one we settled on was attaching the geolocator to the tibia with a metal ring (one size up from the usual size for this species). We found this to be satisfactory when tried on the next bird we caught. Whilst we only managed to fit one bird with a geolocator, we have the attachment method ready for next year when we aim to spend longer, earlier in the season, when activity in the colony should be higher.

Around 420 birds, of 31 different species were ringed in Vardø in 2017. The most numerous species was mealy redpoll, making up roughly 25% of the total with meadow pipit taking 2nd place at 18%. The season started slowly and gradually picked up over the summer, with mist netting sessions at Sundammen and Svartnes from May to July both averaging around three birds per hour, once migration started in August and September both averaged around 12 per hour. The largest catch was 86 at Svartnes on 17/09, mostly made up by a large passage of meadow pipits and mealy redpolls (this number could have been easily increased with more nets). On both this date and on 20/09 at Sundammen we also re-trapped birds caught there as breeding birds in July. So clearly at least some local breeders were still present this late in the season. The first juveniles started showing up in June making up 8% of birds ringed, rising to 18% in July and 92% in August but dropping to 53% in September (These statistics are for passerines only and the August statistic only includes one ringing session so is probably not representative of the true values).

The scarcer captures in Vardø this year have all come from Svartnes. A juvenile two-barred crossbill was finally captured at Svartnes after up to five had been present in the Sundammen area for a week, and others had been observed nearby, representing the first one ringed in Finnmark.

The 86 birds caught at Svartnes on 17/09 included 3 scarcer warbler species: one marsh warbler (the first ringed, and second record for Finnmark), a yellow-browed warbler and a garden warbler.

Also of great interest was that one of the 7 sedge warblers caught, was wearing a Czech Republic ring and had been ringed near Pilsen on 11/09/2016! The bird was one of several male birds that were holding territory at Sundammen in the spring.

Looking ahead

Now in our 6th year of these projects we have learnt a lot. We now know more about which species migrate when, to where; some of the factors that can influence their abundance, and how this differs from other parts of the birds’ ranges. We have also recorded some scarce species which would otherwise have gone undetected. Despite this, many new questions have been raised and we aim to continue and expand our projects in the coming years to try and answer these.

References: Pollet, I.L., Hedd, A, Taylor, P.D., Montevecchi, W.A. & Shutler, D, 2014. Migratory movements and wintering areas of Leach’s Storm-Petrels tracked using geolocators.